Perry Preschool Project

What Was Perry?

The original Perry Preschool Project was a randomized study developed by American psychologist David Weikart and conducted from 1962-1967 to track how the intervention of high-quality early childhood education could positively affect the IQ of at-risk, African-American children from low income families based in Ypsilanti, Michigan. The participants of the project were provided a stimulating classroom education, as well as weekly home visits that were meant to teach mothers how to best support their child’s development by extending the preschool curriculum into the home. The curriculum focused on boosting a child’s non-cognitive skill development (e.g., perseverance, problem-solving, grit), which was thought to be the key to increasing grades and IQ scores and thus breaking the cycle of poverty. While grades and IQ were ultimately proven to be poor indicators of long-term success, the longitudinal effects on participants’ criminal activity, employment, and certain measures of health and non-cognitive skills, as well as effects on the children of participants demonstrated how the project led to more positive adult life outcomes (based on surveys at midlife) which, in turn, led to better equipped parents.

Through the Years

Perry has since become defined as an iconic early childhood intervention, and its pioneering components formed the basis of the HighScope curriculum still used today. Perry is critical in our understanding of intergenerational and social benefits of early childhood education. HighScope, an early childhood educational research group, was founded based on the methods of Perry, and has continued to produce monographs of the Perry participants and several studies since its foundation in 1970 by study director David Weikart. These results carried many implications for policies, including the key finding that the development of socioemotional and cognitive skills play a role in increasing achievement throughout the life cycle, specifically through age forty.

Despite these positive results, the original research continued to be plagued with gaps and uncertainties, chiefly concerning sample size, data flaws, and doubts in the methodology—which focused mostly on incomplete knowledge of and compromises in the randomization protocol—that allowed for considerable criticism about the true efficacy of similar high quality early childhood education strategies, particularly when scaling them. It was still empirically unclear whether the effects persisted later into the participants’ midlife, and whether they could also be transmitted intergenerationally.

New Approaches

In order to address the uncertainties as to the project’s impact and integrity, Center director James J. Heckman and his co-authors worked together to produce three separate papers reexamining the evidence, the imperfect randomization of the original study, and the potential rate of return for the first time. Two of the papers, written in 2010, conducted a more rigorous analysis of the data compared to previous undertakings, and were responsible for smoothing some discrepancies and providing the basis for the “$7.00 return for every $1.00 invested” in children claim, which Obama made in his 2013 State of the Union address to justify investments in early childhood programs. To further strengthen their research, the third paper, published in 2013, showed that the project’s positive effects on socioemotional skills were especially instrumental in producing the reported effects on crime, health, and other factors.

Despite this work being more rigorous than previous studies by others, concerns about sample size and other flaws still remained, creating the need for an even more thorough analysis of the Perry Program and its participants, some fifty years later.

Heckman then endeavored to fully quantify the Project’s impact on participants, as well as their children, over the life course via longitudinal data. Building upon his previous work evaluating the costs and benefits of the Perry Preschool Project, this analysis utilizes a set of data from late midlife (around age fifty-five). In this data set, participants are surveyed on crime, health, earnings, education, and children’s outcomes in order to create an expanded analysis, providing us with the opportunity to understand the effects of early childhood intervention over the life course. Additional information about the original randomization and study design, as well as detailed new data on participants’ siblings and children, offer an insight into the multi-generational benefits of the Perry Project.

What’s New About Our Methods

The methods used in this analysis are especially groundbreaking due to the unique, rigorous procedures designed to address compromised in the original randomization procedure. Analysis at age fifty-five uses the most conservative, “worst case” p-values that explicitly account for limitations of the data sets. Under these randomization compromises, standard inferential methods lead to more false positives than desirable. CEHD’s method, instead, performed much better, with considerably lower rejection rates.

Results

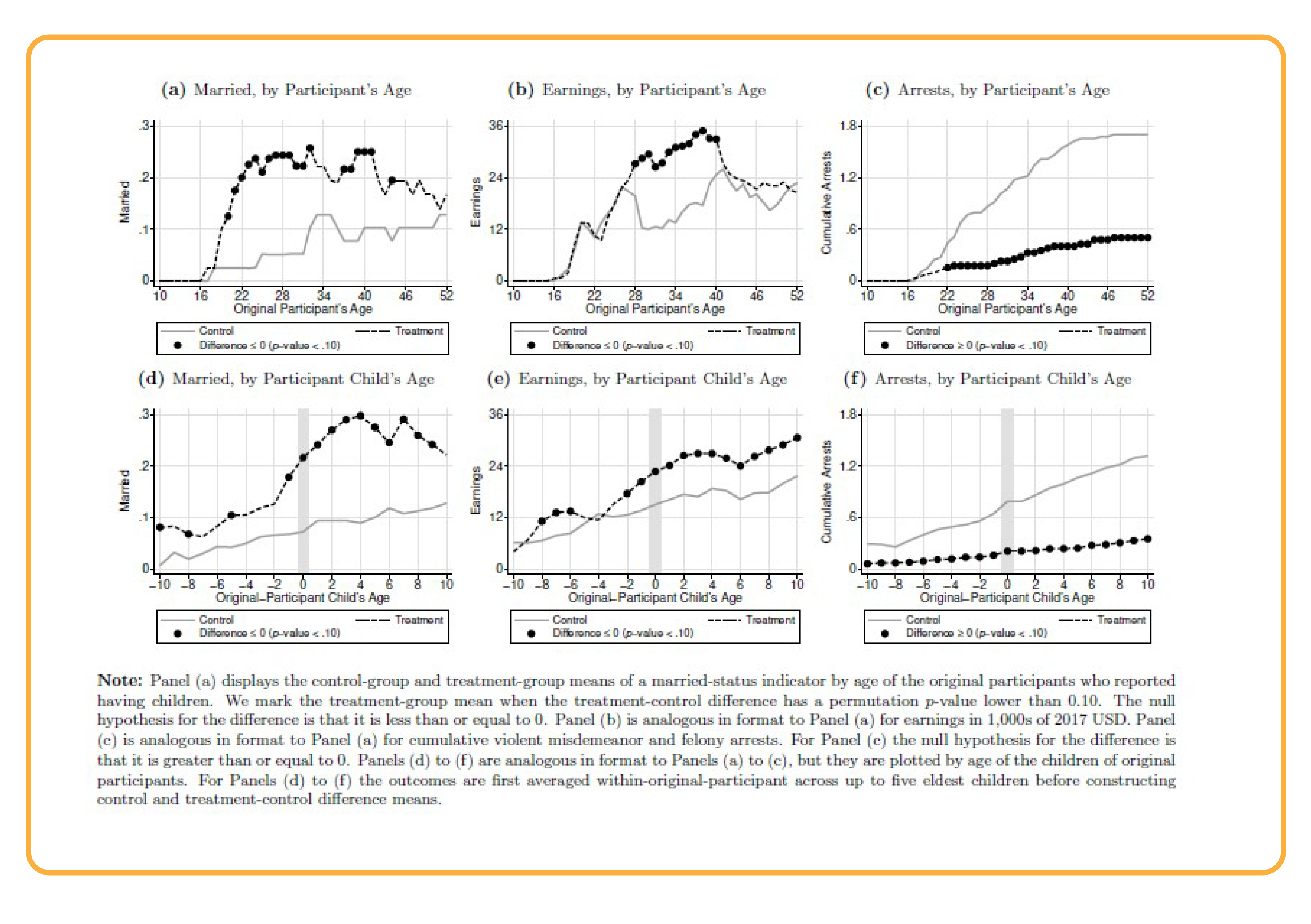

Regardless of the methodological approach, significant treatment effects still emerge on crime, employment, health, and both cognitive and non-cognitive skills of the original participants, with effects most prominent in males. Gains in cognition are sustained through age 54, contradicting claims about cognitive fadeout in the treatment effects of early childhood programs. Enriched early childhood education programs are promising vehicles for promoting social mobility.

The analysis at age fifty-five also looks at the treatment’s spillover effects on the siblings and children of the original participants. The impact on the skills and health of the original participants persists through their childrearing years up to their late midlife years, and their improved outcomes translate into better environments for their children to grow up in. Children of treatment-group participants are more than 10 percentage points more likely to be born to married parents than children of control-group participants.

Children of treated parents are 17 percentage points less likely to have been suspended from school during K-12 education compared to children of control participants. They are also 11 percentage points more likely to be in good health through young adulthood, 26 percentage points more likely to be employed, and 8 percentage points less likely to be divorced. Children of male treated participants are also 18 percentage points less likely to have been arrested through young adulthood compared to children of male control participants. These estimates are statistically significant and robust across multiple estimators and inferential procedures designed to address methodological challenges inherent to the project. There are also substantial positive effects on the siblings of participants, who did not directly participate in the project, suggesting early childhood interventions can have important indirect benefits. These spillover effects add to the benefits and substantially increase rate of return of the program.

These results show that high-quality early childhood education can strengthen families and has the potential to break the cycle of intergenerational poverty. Notably, the children of participants were more likely to graduate from high school, a key determinant in later employment. There was also found to be no fadeout in terms of life outcomes: Perry significantly increased participants’ performance in a variety of measures that continued into the second generation through strong family structures, greater likelihood of providing a stable two-parent home, having children slightly later in life, and remaining stably married by the time children turn eighteen. Despite remaining in low-income neighborhoods, children still benefitted long-term compared to control groups in similar or worse neighborhoods. This suggests developmentally-supportive home environments matter more than neighborhoods for adult outcomes, which will likely change the narrative in policy-making by shifting focus to the household for more effective, long-lasting social effects.

What Does It Mean?

This analysis of the Perry Preschool Project resulted in the discovery that treating just one generation can lead to lasting positive outcomes on following generations. Evidence suggests that the children of the original participants grew up in more stable two-parent families, and their parents had better socioemotional skills, earnings and employment, and lower participation in crime. The rate of social and economic return of such programs is found to be even higher when the next generation is taken into account. Overall, CEHD’s findings support the importance of family and the relative unimportance of zip codes in explaining the observed intergenerational effects on the children of Perry participants. It is high-quality parent-child, parent-teacher engagement and home visits that promote education environmental and socioemotional development.

The study of Perry at midlife adds to a body of work that provides important evidence that high-quality early childhood education between the ages of zero and five is an effective policy tool to help low-income students succeed. While these results are not one-size-fits-all, this research shows that providing resources to develop a child’s cognitive and socioemotional skills can promote long-term and indeed intergenerational benefits. Lower levels of crime, increases in education and income, and improved socioemotional skills are benefits that propagate across generations, and work toward breaking the cycle of poverty.

Working Papers and Publications

The Lasting Effects of Early Childhood Education on Promoting the Skills and Social Mobility of Disadvantaged African Americans

This paper demonstrates multiple beneficial impacts of a program promoting intergenerational mobility for disadvantaged African-American children and their children. The program improves outcomes of the first-generation treatment group across the life cycle, which translates into better family environments for the second generation leading to positive intergenerational gains. There are long-lasting beneficial program effects on cognition through age 54, contradicting claims of fadeout that have dominated popular discussions of early childhood programs. Children of the first-generation treatment group have higher levels of education and employment, lower levels of criminal activity, and better health than children of the first-generation control group.

The Dynastic Benefits of Early Childhood Education

This paper monetizes and aggregates the life-cycle benefits of the Perry Preschool Project for the original participants and the additional benefits accruing to their siblings and children. The program increases labor income and reduces crime and the cost of the criminal justice system. It also improves health and healthy behaviors. Increases in earnings, decreases in governmental safety-net transfers, lower criminal justice and crime victimization costs, and improved quality of life generate the program's benefits. PPP generates 6.0 (s.e. 3.4) dollars of public and private benefits per dollar invested in it. This estimate accounts for the deadweight generated by collecting the taxes to fund the program. The impacts on the children of the original participants generate a substantial additional benefit. Our life-cycle data enable us to avoid forecasting future outcomes in making estimates and to evaluate the accuracy of currently widely used forecasting schemes, which we find wanting.

Using a satisficing model of experimenter decision-making to guide finite-sample inference for compromised experiments

This paper presents the first analysis of the life course outcomes through late midlife (around age 55) for the participants of the iconic Perry Preschool Project, an experimental high-quality preschool program for disadvantaged African-American children in the 1960s. We discuss the design of the experiment, compromises in and adjustments to the randomization protocol, and the extent of knowledge about departures from the initial random assignment. We account for these factors in developing conservative small-sample hypothesis tests that use approximate worst-case (least favorable) randomization null distributions. We examine how our new methods compare with standard inferential methods, which ignore essential features of the experimental setup. Widely used procedures produce misleading inferences about treatment effects. Our design-specific inferential approach can be applied to analyze a variety of compromised social and economic experiments, including those using re-randomization designs. Despite the conservative nature of our statistical tests, we find long-term treatment effects on crime, employment, health, cognitive and non-cognitive skills, and other outcomes of the Perry participants. Treatment effects are especially strong for males. Improvements in childhood home environments and parental attachment appear to be an important source of the long-term benefits of the program.

Figure 1: Original-Participant Marriage, Earnings, and Crime by their Age and by their Children's Age

Project Team

James J. Heckman

The University of Chicago

Project Partners